THE PILGRIMS' BAN ON CHRISTMAS

Christmas Festivities Forbidden in17th Century American Colonies

Massachusetts Bay Colony

Notice of Christmas Ban, 1759

Christmas was once outlawed in Boston, and festive cheer was greeted with a five shilling fine. The Puritanical law lasted for 22 years, from 1659 to 1681.

The American ban on Christmas can be traced back to England. In 16th century England, Christmas was celebrated with religious festivities that included carols and plays, but the holiday was also associated with extravagant feasts, gambling, and drinking. Puritans, who started to emerge in England around the same time, were critical of the excessive celebrations and believed that the holiday demonstrated the Pope’s persistent influence within Protestantism.

When they arrived in America, the first Pilgrims continued to condemn Christmas and defied observation of the holiday by spending the first Christmas in 1620 building their first structure. Soon, however, discordant opinions about Christmas started to emerge among the early settlers. On the second Christmas in 1621, Governor William Bradford started to lead men to work as usual but was met with resistance as “most of this new-company excused them selves and said it wente against their consciences to work on [Christmas] day.” The governor excused the men from working, if it was truly a matter of conscious, and “would spare them till they were better informed.” Bradford proceeded to work, but when he returned, he was angered to find the men playing sports openly in the streets:

So he went to them, and tooke away their implements, and tould them that was against his conscience, that they should play & others worke. If they made [sic] keeping of it mater of devotion, let them kepe their houses, but ther should be no gameing or revelling in [sic] streets. Since which time nothing hath been attempted that way, at least openly.*

In 1659, observation of Christmas through “forbearing of labor, feasting, or any other way” was banned in Boston, and a five shilling fine was imposed on any offenders (see notice above). However, the law was difficult to enforce and as more non-Puritan settlers arrived, tensions over Christmas continued to arise.

Meanwhile across the Atlantic, English Puritans had a chance to act on their anti-Christmas sentiments during the English Civil War, in which the Puritans rebelled against King Charles II. Parliament was able to pass an ordinance banning Christmas, Easter, and Whitsun feasts. Many Englishman, however, were not ready to do away with Christmas, and riots broke out throughout England on Christmas Day 1647. A particularly violent riot broke out in Canterbury and contributed to the start of the second civil war. After Parliamentary victory in the Civil War, Christmas public celebrations were banned, though many shops still closed in protest and private celebrations were difficult to stop. When the monarch was restored in 1660 under Charles II, the ban on Christmas was lifted.

See the OH Article on Valentine Greatrakes, the Civil War, and the Restoration of the Monarchy.

Following suit, the American ban on Christmas was revoked in 1681 by Sir Edmund Andros, an English-appointed governor. Anti-Christmas sentiments still held strong in Boston, though, and schools still remained open on Christmas Day well into the mid-1800’s. Puritan resistance to Christmas finally gave way in 1870, when it was declared a federal holiday.

Julia Chen

First Published 12/11/2014

*Bradford's journal used the formerly common print convention of "Ye" to denote the word "the," where the "Y" replaces the "th." This is the remnant of an ancient Nordic rune called a "thorn," and was the printed representation of the "th" sound. So, "Ye Olde Coffee Shop," would have been pronounced, "The Olde Coffee Shop." See more about the letter Thorn.

PRIMARY SOURCES

William Bradford, History of Plymouth Plantation (Boston: Little Brown, 1856), 112.

Massachusetts Bay Colony Notice of Christmas Ban, 1659. (See above.)

SECONDARY SOURCES

Stephen Nissenbaum, The Battle for Christmas (New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2010).

Penne L. Restad, Christmas in America: A History (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1995).

Rachel N. Schnepper, “Yuletide’s Outlaws,” The New York Times (December 14, 2012).

RESOURCES

PIETRO BELLOTTI

OLD PILGRIM,

1660S-1670S

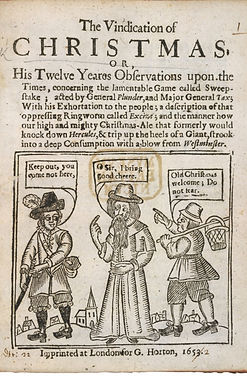

The Vindication of Christmas

Printed for G. Horton, 1652

The Woodcut reads, from L to R:

Pilgrim: Keep out, you come not here,

Man 1: O Sir, I bring good cheere.

Man 2: Old Christmas welcome; do not fear.

The "Pass-cup" or the "Loving Cup"

The Science of 17th Century Pottery

The two- or three-handled "pass cup" was a common form of pottery in the 17th Century, including the American Colonies.

Pass-Cups were intended for communal use, but they also had some ceremonial functions.

Pottery in the colonies was largely composed of earthenware or clay, which could be "thrown" pottery on a wheel, or constructed by hand. Pottery was then "fired" at a high temperature in a kiln then cooled. It was then glazed to seal it and for decorative purposes, and refired.